How to Read Philosophy

Reading is often treated as a binary skill. You learn to read as a kid, and then you just know how to read. This is, however, an oversimplification. Reading different texts, for different purposes, requires different skills. Reading philosophy is a prime example of this. Texts are often dense, technical, and nuanced, and steeped in a literature that you may not have read. What’s more, when you read them for class, you may not know what you are reading them for - do you need to only get the big idea? Do you need to know all the details? Here, I’ll discuss tips for reading philosophy in a few categories - how to prepare to read philosophical texts, how to read like a philosopher, and how to take notes on philosophy.

Preparing to Read

My first step is always a mug of tea (but that is optional.) More importantly, the first thing you need to do is decide what you are trying to get out of the reading. Some possibilities:

Reading for the gist - what is the author’s thesis, and what is the main idea for how s/he argues for it?

Reading for the dialectic - what is the author’s thesis, and how does it relate to the other positions in the debate?

Reading for the argumentative details - what is the author’s thesis, and how exactly does the argument for the conclusion work?

Reading for a particular topic - does the author address any ideas relevant to my current research?

Your reasons for reading will differ, and there is no one answer to this question. If you taking a philosophy class, you are probably being asked to read for the dialectic and for the argumentative details. This is helpful, because it helps you decide which information you’ll need to pay close attention to, and which information is less important. It will also help you decide how to take notes, which I will talk more about below.

Finally, before diving in, give the reading a skim. Now, this is advice that just about everyone has heard before, and advice that is just as often ignored. One common reason to ignore it is simply that it takes time. If your goal is to actually understand the reading, however, a skim actually speed things up! Why? Because it helps you figure out how the parts of the article or book fit together. It’s like reading a mystery - if you read the end first, you’ll be able to tell what all the important clues are, and which details will turn out to be irrelevant. This is no fun for mysteries, but helpful for philosophy. So what should you look for in a skim?

Title: some philosophy titles are obscure, but others tell you the topic of the paper.

The introduction and conclusion: the thesis is often stated in both of these sections.

Section headings: if present, these will help you get a sense of the structure. Are particular sections reviewing the literature? Advancing the authors arguments? Considering objections against their view?

Reading Strategies

The key to effectively reading dense academic sources is to be a reflective reader. This means thinking about a text on four levels:

Textual level - what does the text say?

Meta-textual level - why is the author saying it? How does it connect with other parts of the text? What about with other things I’ve read or seen?

Evaluative level - what do I think about what the author is saying?

Meta-cognitive level - how well am I understanding the text?

Developing reading skill means being able to read at all of these levels simultaneously. It is also not an easy skill to develop! It takes practice. Yet, practice by itself isn’t always helpful. I’m not a very good singer (where “not very good” is a euphemism for “awful”). If I decide I want to improve, singing around my house for hours on end isn’t going to help. I’m just going to reinforce the things I do now. I need to practice doing the right things as a singer. So how can we practice doing the right things as a reader?

The key is learning to recognize when to use different reading strategies, and practicing them in those cases, where they will be most effective:

| Reading Experience | Strategy |

|---|---|

| If, at the end of a paragraph, you cannot give a one sentence summary of what was said.. | Re-read the paragraph until you can, or, if after a couple readings you stil can’t make sense of it, make a note of what you don’t understand to bring to class. |

| If, the author makes a claim that is surprising, or unexpected based on what has come before… | Ask, why might the author be making this claim? Does s/he think it follows from what has come before? Is the author considering a claim only to reject it? |

| If the author makes a claim that you think is clearly wrong… | Ask yourself - why would the author make this claim? What are the best arguments s/he would offer in favor of it? |

| If the author is sign-posting, or telling you either what s/he has already done, or telling you what s/he will do next… | First, make sure that this fits with your understanding of where the paper has gone, and where it is going. If not, go back and re-read! Second, note the pasage, and as you keep reading, make brief notes in the margins where the author does what s/he said they were going to do. |

| If the author uses a term which you do not know… | Look it up. When reading philosophy, you might want to start by checking if the author defined the term - sometimes terms are used in specific ways. If not, then check a philosophical dictionary, or encyclopedia. Philosophical terms are often used differently from the definitions you will find in the dictionary. |

| If I notice the same concept or idea coming up over and over.. | Pause and make sure you can explain that concept, and give an example of it. If you can’t, make a note of your questions, and look for answers earlier in the text, and as you keep reading. |

Taking Notes

The reason you are reading is again crucial to making good decisions about taking notes. After all, you don’t take notes just to have something written down, that you can tuck into a folder or notebook and never look at again. You should take notes for a reason, and that reason will dictate what your notes should focus on. For example…

If you are preparing for a test, reflect on what information you’ll need to know. Author and thesis? An overview of the argument? Will you need to be able to apply the author’s view to some new idea? If so, perhaps you’ll want to focus on examples and how they relate to the core ideas.

If you are preparing to write a paper, you’ll certainly want to know the author’s thesis, and an overview of the argument. You may also want to note good passages - references to text you might cite or quote in your paper. Perhaps you’ll also want to focus on jotting down connections to other texts, so that you can explore them while writing. Most importantly, you’ll want to be writing down your own ideas, as these ideas might be the basis for your own thesis when it comes time to write the paper.

If you are reading for a general understanding as part of a literature survey, then, in addition to the thesis and argument, you should write an abstract for the reading. This technique helps you to consolidate your memory of the essay, in particular by asking you to focus on what was most important.

Before turning to some specific methods, there are a few general tips that apply no matter what note-taking method you decide to use:

Don’t simply highlight passages. Highlighting should be used to supplement other methods. The two problems with just highlighting are that (1) it is a passive note-taking strategy, which doesn’t really help you remember or make sense of what you are reading, and (2) it is harder after the fact to make sense of why you highlighted each passage.

In addition to your contemporaneous notes (the ones you take while reading), take notes after you finish. This could be re-writing notes into more coherent and clearer sentences, writing a short summary of the reading, etc. What is important is that you take the time to make sense of the entire reading after you finish, it will help you commit your notes to memory, and to think about the reading as a whole, and not just as a series of smaller parts.

Once you know why you are taking notes, you can adopt some of the following strategies. I’ve included three strategies below. Finding the right method is mostly a matter of personal taste - what is important is that you find a way that helps you achieve your goals as a note-taker.

The Philosophical Cornell Method

This method uses an adapted version of the Cornell Method. There are three parts to your notes. In the largest box (on the right), you take your notes on the text. What is the author saying? In the smaller box on the left, you write down your own thoughts. What do you think about what you are reading? Finally, at the bottom, you write a short summary of the reading.

You can find a blank template for this method here.

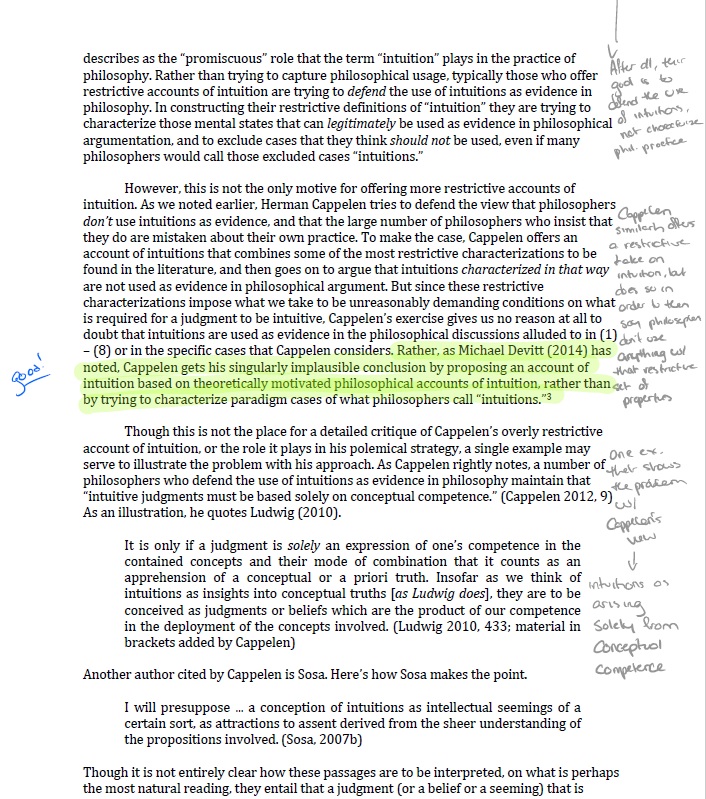

MARGINALIA METHOD

To effectively take notes in the margins, I use one color for my own thoughts, and another for summaries of what the author says. I then use the highlighter for key claims, and passages I may wish to draw upon later.

You can also use custom symbols that indicate things like questions, or objections, that you elaborate on in another piece of paper. You can find one good set of symbols, developed by Marc Busser at McMaster University, here.

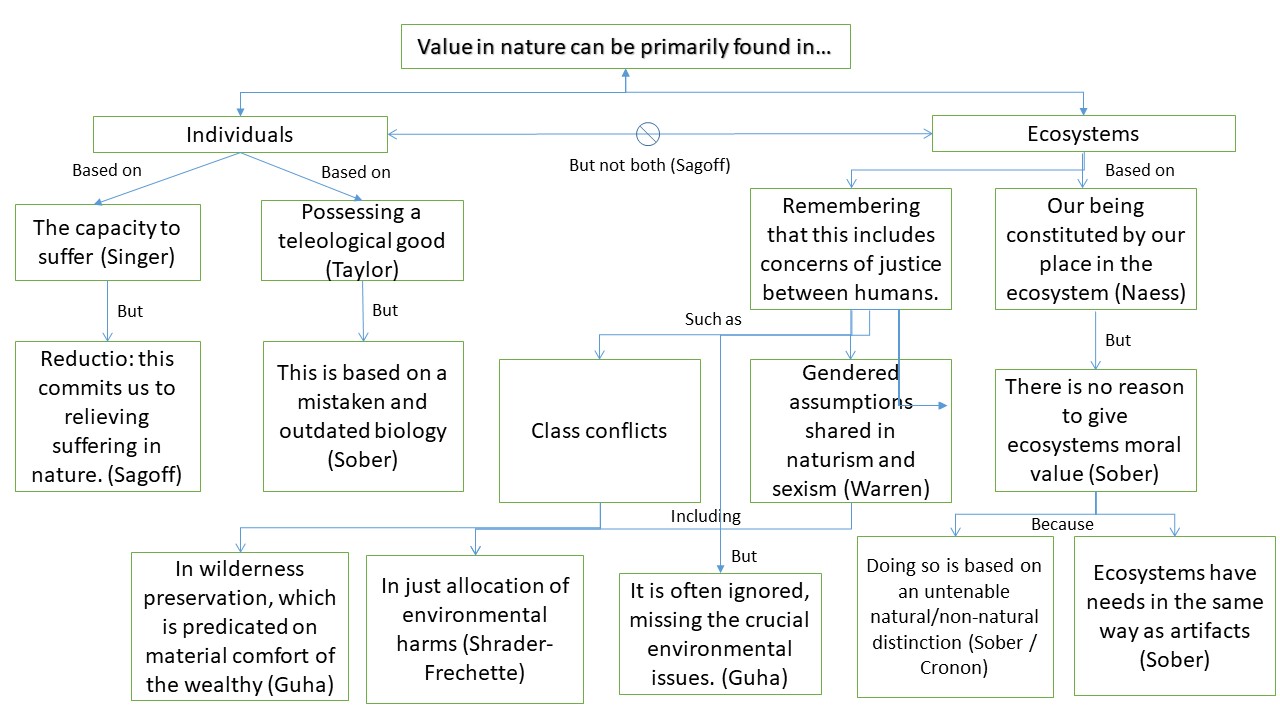

Concept Maps

A concept map is a visual representation of the ideas discussed in a text, or relating different texts. First, start with a list of the key ideas. Then, decide what relationships you want to use, such as “supports,” “opposes,” “develops,” etc.

You can do these on paper or on the computer. One advantage of doing them on the computer is that you can move boxes around to try to figure out where they all go.